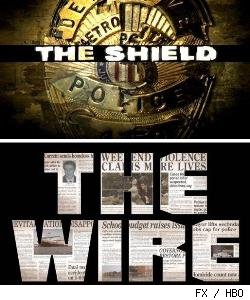

My unofficial job title for the last couple of months has been PR Officer for American TV. Recently I’ve been introducing G to a number of my favourite US TV shows using the vast-if routinely inaccessible-archive of programming on Netflix and HuluPlus as well as my DVD collection, which lies within a handful of colossal CD carry cases in an object-fetishist’s version of efficient storage. Some programmes sold themselves. It didn’t take long for G to figure out that Northern Exposure was an engaging, endearing and intelligently written piece of television and not the geriatric-baiting fodder she suspected. Despite its nausea-inducing camerawork, the viscerality, complexity and wit of The Shield also won G over instantly. But there was always a fly in the ointment, and in every application. G took issue with the titles of both shows, Northern Exposure for its meandering moose and The Shield for its kid-friendly jingle. I tried to explain that these were some of the most iconic and beloved aspects of these shows but it fell on deaf ears and blind eyes. Much as I love them, I can see why G thinks these gimmick-driven, one-dimensional titles might be doing a disservice to the shows.

‘Stupid moose’-G

But sometimes G’s sales resistance is difficult to break down. Her response to the Pilot of Breaking Bad was ‘That’s it?’. I wanted to argue with her but it did seem slight in comparison to later episodes and I didn’t think my observation that it was a ‘postmodern version of MacGyver’ would make it seem any more profound. Twin Peaks was apparently ‘all dialogue’, which is a new one for Lynch critiques, and only became visually stimulating when the donuts came out. In these instances, I did what every good salesperson should and tried to associate the product with something the customer knows and likes. ‘It’s like Northern Exposure…but with murders’ I said of Twin Peaks. ‘It’s Malcolm in the Middle on meth’, I said of Breaking Bad. ‘You watch Malcolm in the Middle? What are you, 10?’ G responded. I guess my cold reading skills aren’t as good as I thought. Or maybe the prospect of Bryan Cranston in underpants isn’t as alluring to the rest of the world as it is to me.

Just me, then…

On other occasions I became a victim of my own salesmanship. I’ve managed to hook G on a hoard of arresting novelty shows that I’m fast losing interest in. This means I’m watching their tiresomely protracted runs again as exactly the point when I’ve given up on them. 24 and Damages are the chief culprits here, both of them wildly overlong elaborations on an initially brilliant premise. I didn’t think I could lose much more respect for 24 than had already gone but sitting through those final few seasons again with their automated scenarios and tedious twistiness I think it went subterranean. Worse, as the gruesome compulsion to clear all the episodes in as little time as possible accelerated, the show became like wallpaper in our house, an ever-present wall-adornment barely noticeable to our jaded eyes. G is still at the point in Damages where the promise of finding out what will happen in the ongoing story arc is yet to be beaten down by the knowledge of what does happen. But I can see this fading fast. G’s already worked out that they’re only keeping a serial story strand so as not to lose Ted Danson from the series.

A reason for sticking with Damages.

Although G came to Mad Men much later than me, thus allowing me to cherry-pick the most tolerable episodes from the dreary first few seasons, we’ve both turned sour on the series at about the same time. Actually, G got there first before I was willing to admit that the party was over. Midway through the most recent season, the sixth overall, I remember her asking ‘Where’s the advertising gone?’, which should have been enough of an alarm bell given that it’s the equivalent to Cheers forgetting to feature beer. For me, though, it was the sexual reunion of one of the series’ estranged couples that signalled the end of quality. Breaking a rule of good television established in Northern Exposure, it haphazardly thrust (in every sense of the word!) two characters together whose entire function was to carry the suggestion of romantic involvement without ever reaching that point. G turned to me the other day and said ‘I miss British TV’. I think it might be time to start offering a new product line.

If you like these blog posts why not follow my new twitter account @tvinaword where I create new words to describe TV shows. Send your own and if I like them I’ll retweet them!