In an interview with the BBC some years ago, Sopranos creator David Chase, speaking of his first writing gig on The Rockford Files, remarked that what set the private eye series apart from most TV at the time was that it was recognisably set in Southern California and not some ersatz non-place. This innate sense of place trickled down into Chase’s later TV work. One look at Jersey Shore and The Real Housewives of New Jersey and it’s obvious that the landscapes and body shapes that feature in The Sopranos could only be from the Garden State. It’s also something that distinguished Rockford creator Roy Huggins’ TV shows. His previous creation The Fugitive (one of the other only TV programmes Chase admits to enjoying) was always specific in its geography, be it small town or vast metropolis, no mean feat for a series which had to change location every week.

Jim Rockford, a resident of Malibu

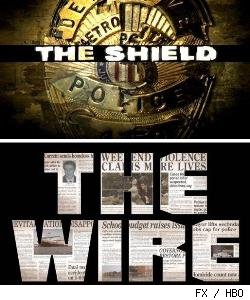

Place is increasingly becoming the backbone of American TV. The unique appeal of shows like AMC’s Breaking Bad is inseparable from their choice of setting. The meth-drenched desert hazes and border town hinterlands of Albuquerque provide not just a backdrop to the action but the pathetic fallacy of the characters’ moral decay and corruption. Other programmes like Portlandia build their very concepts around a place rather than a set of characters or situations. It may be that the IFC sketch show starring Fred Armisen and Carrie Brownstein relates to something bigger than just the Oregon city-like the hipsterfication of everyday life-but such observations are always squarely aimed at Portland’s grunge-throwback ways. The Wire (and the lesser known but not lesser in any other way Homicide: Life on the Streets) may speak to people as a microcosm of American social problems but in the end it’s a programme about a place, Baltimore, Maryland, and impossible to truly appreciate without a working knowledge of that city’s local political scene. So is this a new development in American TV and, if so, what changed?

The dream of the 90s is alive in Portland!

It’s tempting to put the recent emphasis on place in American TV down to historical shifts in the way that programmes are produced. For much of its existence, TV was filmed predominantly in studios making it difficult to manufacture an authentic impression of place. When location shooting was added into the mix, the ability to suggest events were taking place in a distinct locale improved drastically, even when programmes were still studio-bound. Cop drama NYPD Blue seemed firmly planted in the many and varied neighbourhoods of the Big Apple despite being the majority of it being filmed on the Fox backlot in L.A. simply because of the documentary-styled location footage of the ongoing life on New York streets that pre-empted each scene. Now that the technology of production has advanced sufficiently to shed the studio, putting place at the centre of a TV show should be everywhere by now, right?

NYPD Blue or LAPD Blue?

Possibly not. Location shooting is used more readily to invite a sense of reality without necessarily specifying the geography. It was used in Hill Street Blues to project a (radical) urban grittiness but stopped short of saying what city events took place in (we can assume Chicago but are never told for sure), even going as far to create a fake district of this unknown metropolis. The ability to film on location doesn’t always mean you can film anywhere you like. Think about how many American TV shows are needlessly set in the vicinity of L.A. Often this isn’t an artistic choice but a local one. It’s plainly easier and more economical to find somewhere to shoot near the production base, in this case Hollywood, and use that to justify the setting. It’s the only way to understand why a show like 24 about federal counter-terrorism agents is set in the City of Angels and not Washington or some more suitable hub of government activity.

24 in L.A…for some reason

It’s clearly still a choice at the discretion of programme makers whether or not to push place and yet it’s happening more and more. I’m not sure what the explanation is. Perhaps it’s a product of multichannel television narrowcasting to niche audiences, allowing programmes about specific parts of the US to become popular regardless of broad national appeal. Maybe basing a show around a place is another way to create a programme’s distinctive brand in an ever-more competitive market. Most commentators agree with Chase that a sense of place is a sign of television quality. It’s certainly more important than it used to be.